Wednesday, September 21, 2005

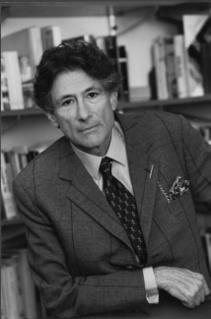

Edward Said’s Brilliance Lives On

THE FILM “Edward Said: The Last Interview,” directed by Mike Dibb, was screened July 13 at the Palestine Center in Washington, DC as part of the “Voices of Palestine Summer 2005 Film Series,” sponsored by the Jerusalem Fund and the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University.

THE FILM “Edward Said: The Last Interview,” directed by Mike Dibb, was screened July 13 at the Palestine Center in Washington, DC as part of the “Voices of Palestine Summer 2005 Film Series,” sponsored by the Jerusalem Fund and the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University.Said stopped giving interviews in the latter part of his life, making this final interview, with Charles Glass,particularly significant. In it he discusses his childhood, politics, his career, music, literature, and even his disease. After being diagnosed with leukemia in 1991, Said became increasingly weak, and spoke of his frustration with losing energy when he wanted to work. When he got tired while working, he said, “a picture of Sharon” flashed in his mind, giving him a “shot of energy” to keep going.

During the October 1973 war, he said, everyone in New York—where Said lived and taught at Columbia University—identified with Israelis as “we” and depicted Arabs as the enemy. This caused Said to become particularly interested in “the battle for representation in the Arab world,” and resulted in his book Orientalism.

He proceeded to discuss the evolution of his work since Orientalism, his interest in broadening the territory of anti-colonialist movements beyond the Arab world, and his arrival at the conclusion that “nationalism itself is not enough for independence.”

He also explained his inherent attraction to difficult areas such as modernist literature, music, the role of the intellectual, and the question of Palestine, which he characterized as “not only difficult but almost impossible.”

Said returned to “Israel” in 1992, and said he was frustrated by the idea of how it was “possible to just transform a place.” Describing the Oslo accords as “a sham,” Said noted that he was opposed to them from the beginning, whereas it took most of the world years to realize Oslo’s shortcomings. He criticized not only “the inability of Arafat and his people to protect their own people,” but the absence of living Arab role models, lamenting that those Palestinians who are “superbly educated” were “the ones who are always flirting with Arafat and wanting to get a cabinet position.”

In Said’s opinion, the only hope for peace would be a single, secular state. “Israelis would probably be OK with this,” he speculated, but American Jews would be an obstacle, since, he explained, they idealize Israel as a religious retirement home. Said described their desire to have a “purely Jewish state” as “purely fantasy,” since, he explained, “if you can’t admit into your consciousness the existence of another people, then you’re really on the way to ruin.”

While this latter condition applies to both Israelis and Palestinians, Said attributed the failure of peace and the ongoing violence to the fact that, ultimately, “all that’s being offered to [the Palestinians] is that they negate themselves.”

—Tara Ahmadinejad

Washington Report on Middle East Affairs