Thursday, August 24, 2006

Mary Rizzo - The Plug-in Man and Immigrant Skin

It seemed like quite an absurd proposition when the Situationists wrote it in 1964, but reality had a way of catching up with their conception of man’s course in the post-industrial world. When they were writing that the future of the modern man was to simply fulfil his role as a vessel for reception and transmission of information, that his mobility would be superfluous, it must have seemed completely ridiculous in the light of the industrial and technological development going on at that time. How could such an absurd proposition be taken seriously in the age of supersonic jets, streamlined cars, even rockets that shot humans beyond the atmosphere? It was commonly assumed that the future was mobile. Advanced man was on the move, after all, and any nomadic peregrinations he might still attempt were made at the speed of light.

It seemed like quite an absurd proposition when the Situationists wrote it in 1964, but reality had a way of catching up with their conception of man’s course in the post-industrial world. When they were writing that the future of the modern man was to simply fulfil his role as a vessel for reception and transmission of information, that his mobility would be superfluous, it must have seemed completely ridiculous in the light of the industrial and technological development going on at that time. How could such an absurd proposition be taken seriously in the age of supersonic jets, streamlined cars, even rockets that shot humans beyond the atmosphere? It was commonly assumed that the future was mobile. Advanced man was on the move, after all, and any nomadic peregrinations he might still attempt were made at the speed of light.But if you take a look at where we are now, it seems obvious that the modern man is stuck in one place. And if that is not enough, his experiences are ever more vicarious, as he is plugged in from morning to night. He wakes up with the iPod speakers stuffed into his ear, his cellular phone vibrating on the table, receiving text messages, while he is booting up his computer to start his day of work or pleasure. At a certain point, the body is not really utilised, it is “maintained” as a container for the reception, storage and diffusion of information. His body is structurally a shell to house an optical nerve, some sensors on the fingertips and an aural cavity that retrieves data that is emitted in a repetitious way, usually being information that the brain is already fully aware of.

It seems that the race for mobility was a mere parenthesis between the stasis of man through lack of means of transport (or need to move) and the conscious decision to adopt a lifestyle which has become the mainstream, of allowing the body to assume a passive state. There is an old Senegalese saying that is famous in Animist circles. Since there is the belief in cyclical regeneration of the “essence” of a person, who is reborn after several generations into a new body, one says, “the man is inside”, meaning, the spirit, the being, the person, is present within the transitional state of assuming the shape of a new body, in the substance of one of the descendants. A form of ancestor worship is practiced, since one would be dealing with the essence of previous generations under a new guise, and making peace with the ancestors was also a social lubricant for the people one was in close contact with. The body, in such an extreme case, assumes the role as the container for the symbolic presence of a previous generation, while adding on new experiences to this fully complete being. What counts is inside, the vessel can change, but the message is the continuum of a society and its people.

Who is this “man inside” of the modern man? Does he serve any real purpose? What remains of the purpose of his body? Is each body an end in itself, representing a biological journey and nothing more? Does the person represent a “whole” individual, or are we hopelessly fragmented, emptying ourselves of meaning as we become the transmitters of content that is worth little to nothing, as changeable as last year’s fashion? Is the body capable of being redeemed as a meaningful entity? Or has it become the most modern of messages in itself?

It is simple to recognise that all humans everywhere have the same basic needs and the same drive to have them fulfilled. They are food, shelter, protection and a form of social organisation that presents the limits and extremes in providing for these needs. Fulfilling desires then follows, using the residual energy to do so. If one is fortunate enough to be born in a situation where the basic needs are provided for with little effort, that happy accident permits more of this differentiation of energy and allows one to dedicate oneself to other aspects of life, including leisure. In fact, a certain prolonged neoteny was helpful in evolution, guaranteeing longer care of infants of the human species, and it seems that from this derives the ludic obsession of adults. The priority of guaranteeing needs and fulfilling desires are mixed in one confused drive. And what is more, the line between work and play is growing ever thinner, becoming precisely the perfect environment for the new man, the plug-in man, to thrive.

The fantasy world of children on the surface seems to be pure leisure, where the child is ignorant of the difficulties in procuring the basic necessities, but, actually, it is a gymnasium for providing strategies to acquire the necessary and the superfluous that is nevertheless desired. The child lives in a world of repetition, and this also prepares him for a future where routine becomes the standard. At times, though, the child makes a leap into an unexpected situation, something extraordinary happens in his mental world, and that discovery is exciting, until it too becomes a routine. This is how people learn, acquiring new cognitive information and then integrating it. But, first, it has to be noticed, it has to be in some way attractive. If it isn’t entertaining in the first place, it usually is abandoned. The task of development is to acquire more and more information, and gaining a vast quantity of information, even fragmented, even trivial, is a tendency of modern society. Actually doing something with this information that has been assimilated is not really the point. No one seems to know how to start a fire using sticks and stones, and other tasks primitive man was skilled at, but we all know some details about Angelina Jolie’s lovelife, or other somesuch useless facts. This information is even a market commodity, as gossip is a huge part of the entertainment industry and develops and shifts capital.

By using information on how learning takes place, accepting the idea that surprise, pleasure and fun are emotional aids in acquiring new information that leads to acquiring survival strategies and skills, we see the end result that much information is presented in the form of games or entertainment. It also may explain the way it is easier for man to come to terms with settling into a “virtual world” and limiting movement to the bare minimum for survival, while actually, thriving economically and at times even socially in this state of apparent isolation and stasis. As long as someone is plugged in, the surprises are few, as well as the risks, yet the plug-in man is convinced he is sitting on the cutting edge and is deeply aware of the “latest” information, and therefore, more advanced.

Yet, there is a great risk in all of this. The plug-in man may have more information at his disposal, but he is not equipped to process it, retain it or utilise it in a meaningful way. If one has a computer that does all the calculations or a thesaurus at the touch of a button, what work does the brain really do? It doesn’t need to wander through the meanders of memory or creativity. Solutions are those that are the expected and standard ones. Also, if information regarding a massacre is presented in the same way, with the same emphasis and the same drama as the premiere of a new Hollywood movie, the lines blur as to the relationship of these things to one another and to anything else. We become less able to attribute value to things. It all weighs the same. We lose sensitivity not only in our bodies, but even our capacity to think suffers a major blow.

Another method of information acquisition is more traumatic than playful. Anyone who has been burnt accidentally is careful before they approach flames again, the message is acquired through displeasure and pain. Sometimes, that information is far too widely approximated to similar but unrelated stimulus. For instance, the Egyptians say, “The man who has been bitten by a snake is then afraid of a rope on the ground.” We tend to transfer our reactions to things in a very inappropriate way if we think we are preserving ourselves.

In a way that is similar to acquisition of new information through an event that is out of the ordinary, people unfortunate enough to have been born in a land which suffers a state of poverty, war or political unrest find that the “extraordinary event” that breaks the routine of struggling to survive is often migration. Not only refugees must physically uproot from a place, but even those who seek work in another economic reality are often forced to take leave of their homes. It seems that the less opportunities one has, and the more one suffers from poverty, the more likely it is that a physical move will be prospected. At that point, man moves through space, abandons his land and culture and becomes a commodity.

Immigration is not a situation measured in human terms, as needs being fulfilled and desires addressed, but rather, it is looked at in the point of view of the impact it makes on the market of the target country. These men and women are labourers, providing services, but aside from that, fairly separate, not integrated into the new reality and almost invisible. Mass migration has always been a common occurrence in the human story, yet, in modern society, where borders are drawn up and nations created and destroyed through peaceful or violent means, it thus defines, sometimes by arbitrary means, the belonging of a people and ties them into a national framework. Mass migration carries meanings that touch upon international law and humanitarian issues, since a human is free to leave the place he comes from, but once he leaves that place, he is subject to laws and restrictions about being permitted to enter someplace else.

I am speaking generally of the people who are part of the phenomenon of mass immigration, meaning that numbers of people leaving a country is statistically significant, and can’t really be compared to the businessman, professional, artist or student who goes abroad as an independent decision not based on need, which is the case of people who are more affluent than the average citizen of the country they are leaving. Those individuals who can be considered as part of a mass immigration movement at times assimilate into the new society, but that is not something the society really makes much of an effort at encouraging, and in most cases, the law of the target nation makes prohibitively difficult, especially if the originating culture is quite different from the dominant one, if the market can’t accommodate the services they may offer, or if they are considered to be of inferior ethnic origin. The Rom (Gypsies) generally live in extensive camps on the outskirts of major cities, often for generations and integration is not attempted, even if the municipal entities establish areas for these people to live, becoming a permanent part of the urban landscape. Palestinians are excluded from returning to their land in Israel, and even persons of Palestinian origin, but holding other kinds of passports are forbidden to reside in Israel. The same cannot be said of Jews holding any kind of passport. They are not only permitted, but encouraged to emigrate to Israel and to the territories of Palestine that Israel occupies.

In Europe, immigrant groups such as Chinese tend to develop a parallel society that mirrors the one left in Asia, also creating an independent market that is partially inserted in the local one. African immigration is comprised (at least in Italy) generally of single men, or married men who arrive alone, who work in Europe for years varying from three to ten, organised in self-sustaining social units. Eastern European immigration is widely feminine, where they work in the “family services” industry of nursing the elderly and other domestic tasks, most of the wages sent away to support the family back home. At any rate, it seems that even when a person comes to a new society, often lives as a member of the same household in the target country, there is generally a separateness that is observed and there is a strong link to the people and place of origin that is maintained in a social and economic way. There doesn’t seem to be much true integration, from either end of the spectrum of immigration.

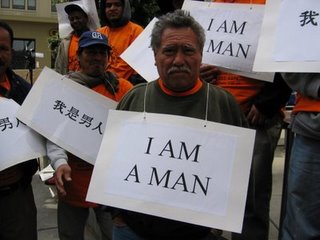

The body of the immigrant differs not only in a superficial way, with colour of skin or style of dress, but it also moves differently. It is an active body, it has moved in space in order to reach the new land, and it continues to differentiate itself by not plugging itself in, but at times, to go even further to enhance the physical existence by symbolic means.

Ritual scarnification, tattoos, piercings, body painting in henna and traditional hair styles such as dreadlocks are symbolic images of the human presence, of the man within, that in Western society have been more and more accepted by the younger generations who are torn between the two paradigms, the passive and the active. Adopting these symbols that carry spiritual meaning in other societies has become a mass phenomenon and no longer transgresses many of Western society’s rules of decorum, but the symbols are chosen to embellish the superficial, not to represent the interior. Does a young man who sports dreadlocks know the reasons the Rastafari use this style? Does it matter?

The only way I felt I could comprehend the feelings that a person in immigrant skin would have, and view from a different perspective the relationship an immigrant might feel with an Italian was to enter into that state of being for myself. I tried an experiment in the open air market of my city in Italy last week. Since I am myself an immigrant, but of Italian origins and fully assimilated due to a permanence in Italy dating from the late ‘80s, I still wanted to feel what it might be like to have immigrant skin, to be looked at as someone who was from a different culture. I asked a practicing Muslim friend of mine to lend me one of her scarves and show me the right way to wear it. We walked through the market, chatting and stopping at various stands and I must admit, I did not become a Muslim, nor did I become an immigrant from an Arab country, but I “felt” different, I felt a stronger attachment to them as a group, I felt part of something different. As different as perhaps many who have a Maori tattoo emblazoned on their skin feel from the dominant mass. For a white person in Europe, perhaps this is as close as it gets to entering into a different body, a different being, expressed in the way others perceive you as being different. If one tunes his sensitivity to that he may start to feel this separateness as a strong sentiment. I am not prepared or able to document all the subtle differences in how I was looked at or spoken to, and there were differences I perceived, (and I think I was more surprised at seeing my friend’s reaction, as she was having the time of her life and was playing the game to the hilt), but this was just an initial experience, an experiment, my first leap into immigrant skin, while I know I am a plug-in woman. It was an attempt at regaining primary sensations, a new identification, which is what may drive many to follow the fashions of adopting non-Western embellishments that are more or less permanent.

The next thought, and the most radical one, is the extreme symbolic use of a body as a message. We can take the example of a person who commits suicide. The mental events leading to this moment are individual, even though depending upon circumstances and individuals, the motivations may even be caused by identification with a collective entity, which is a social, religious, ethnic or national group. Everyone who has decided to take his own life, whether for personal reasons such as a disappointment in love or an economic failure, or as a political act, is leaving behind a message. That body will have to be confronted by others, because it leaves in its wake a change in the reality surrounding it. The body, in that sense, is leaving a message. “Enough” is what it is saying.

The body, absent of life, of the interior that gives it meaning in the general conception of the body as the means in which the interior, the spirit, the soul, the essence – whatever it is that differentiates us from those in a vegetative state, has become the pinnacle of meaning itself.

Since almost all societies value human life, and therefore have been required to attribute meaning to suffering, pain and death, it is always necessary to give a value to the suicide. It gets interpreted by those who are left to confront it. Whatever the reasons why that person had decided to take his own life, we are faced with the task of decoding the message that he or she is leaving us. The body assumes a totally symbolic worth when there is no life in it anymore, but now we have become protagonists in the event, as we are left with no choice than to break the symbolic code and then assign a value to it. The value can be positive, negative or somewhere in between, depending on how we read the act that has taken place, whether we can accept the residual consequences, including violence caused to others.

The target of this message could be a single person, or the entire world, and the more the person who uses suicide as the means to express something political, the more that person identifies himself with the group of people he has undertaken to represent and the concept of individuality becomes less important. It is not necessary to “be” in the conditions of the person one identifies with, but it is necessary to fully feel responsibility towards them and to feel a duty of serving as their ambassador. The identity of the “self” is subservient to the identity of the “group”. Whether or not this person is truly representing this group is not really important. What matters is that he or she is convinced of this, and the mental state leading to the act could also be a moment of total clarity, devotion and generosity. Many societies and religions have the figure of the martyr who sacrifices himself for the common good. It is something that has accompanied mankind for most of its history, and the value attributed to it is higher in the societies that recognise the sacrifice as being in favour of its members. The three monotheistic religions all recognise these figures, almost all traditional and antique religions have used sacrifice as an instrument for creating balance between the sacred world and the world of men. Even secular modernists recognise the sacrifice that the Resistance fighters have made for their people.

As outsiders, there are many ways to interpret this particular symbol. We can react to this in a haphazard and impulsive way, absent of reasoning, like the man who is afraid of a rope, and always mentally assign the meaning of the trauma we are associating the act with to the symbol of the lifeless body, or we, the spectators should feel compelled to attempt to find the true interpretation, and not see snakes where there are ropes. We can call all suicide bombers terrorists, we can determine that what they have done is always to be condemned, and more than that, we can have the arrogance to insist that we have the right to do such a thing as condemn it, as if the values that we hold in place, the word “life”, meaning a life that brings pleasure to us as individuals, can only be interpreted in the way we do it, safe in our affluent, needless worlds.

We can also take another road, rather than assume we can assign our value to an act that is done by someone from a group that we don’t belong to, or whose choice is at the antipodes of what we ourselves would do, we can try to read whatever the message that the person who took his life was trying to leave for us was. We can decide to abstain from judgment, assimilate this symbol, with all that we know about what brought about that act, and try to do whatever we can to prevent that such a situation comes about, that humans should feel that their purpose is to serve as a symbol to leave messages to other people, that they feel the necessity to sacrifice their lives, causing death to themselves as well as death and suffering to others in some instances. We can recognise the core of this act, and get up from our chairs and make an attempt to change the conditions from which it germinated. That means we have to look behind the act, understand it within a context and take responsibility for it.

Are we ready to admit that there is a relativity to values we believe are universal? Can we make that detachment from the values we personally hold dear in order to open our minds to the possibility that what we claim as universal is really only our view of what may be preferable, but is certainly not true for one and all? Will we feel worse if we accept that things are uglier than they look, that life can truly be miserable after all?

It is often the case that some of these messages are launched by people living in immigrant skin. Perhaps they themselves are not living in an unbearable situation where they cannot function in society, but they so strongly identify and feel unity with their group, that it is possible for them to undertake the causes and frustrations of the group they feel that they represent as their own. These persons perhaps also feel strongly the alienation of themselves as individuals, and the difficulty of being fully integrated or assimilated in a place where they are different, or at least feel different, in a world where people are suspicious of difference.

The plug-in man is often the prime recipient of this message. His safety is threatened, and ways of enhancing the impact of this state of discomfort are often manipulated by those who are afraid of the actions, and the capacity of action of the person in immigrant skin. I have always found it ironic that in the USA, crime caused by guns kills many more people than terrorists do, but no one seems to be really panicking that he or she may end up at the nasty end of their neighbour’s bullet, while they look with suspicion and fear at people with biscuit-coloured skin and black hair who board busses, planes and subways with them, as if this person’s presence is the real menace to society, and much more dangerous than the DIY vigilante or common criminal living on everyone’s street. Playing on the technological bent of the plug-in man, we had the Millennium Bug, then 9/11, then the threat of WMDs. All of this has allowed Big Power to slide right in where man feels most vulnerable, allowing him to be spied upon, controlled, recruited, brainwashed and constructed into the perfect element of the machine. Protect your home! Protect your family! Protect your computer! Protect your country! Yes, the plug-in man is reading all of the messages his master forces upon him, picking most of them up while he works and plays and retrieves information, and has stopped really looking at the world as it is. He is closing himself in a protective shell where no one can get in. Yet, there is a danger there. It could happen that the safety that initially was felt starts to feel more and more like a prison where the mind is closed in, followed by the body.

If the plug-in man wants to regain his freedom again, he has to be willing and able to be in touch with what is different, apart and alien. He has to start to take off some of the interference and begin listening to others and himself. There has to be room left for independent thinking, not just recycling of a preconceived message. The plug-in man may not regain full use of his body, but he should learn to read symbols as if all that existed about the body was its means as a communication of a message. Perhaps he could try to learn what it is to live in immigrant skin.

This article first appeared on On Line Journal http://www.onlinejournal.com/artman/publish/article_880.shtml